Food labelling: an overview

For industry, food labels provide marketing space, while for governments food labels are a potential public health tool. There are a range of mandatory requirements and voluntary initiatives that shape how nutrition information is presented on packaged food and beverage labels.

Key Evidence

Back-of-pack nutrition declarations are mandatory in many countries and in Australia and New Zealand a Nutrition Information Panel and Statement of Ingredients are mandatory

In Australia and New Zealand, manufacturers can make voluntary claims on food packaging, and there are some specific rules around nutrition content claims (such as ‘low in sugar’) and health claims

Government-led, mandatory front-of-pack nutrition labelling can be used to promote healthy diets

In Australia and New Zealand the voluntary Health Star Rating system has been in place since 2014

Packaged and ultra-processed foods make up an increasing proportion of diets around the world. It can often be difficult for consumers to assess the nutritional value of packaged foods, many of which contain high levels of added sugars, sodium, and saturated fats. The multitude of product options, and various claims and marketing placed on product packaging and in associated advertising further complicate consumer choices. The increased consumption of highly processed food and drinks high in added sugars, sodium and saturated fats is widely recognised as a contributor to the global rise in overweight and obesity rates.1

Nutrition labelling is important to inform and guide consumers. Nutrition labelling also has the potential to encourage food companies to create healthier products.2 Recent developments in food labelling policies are largely focused on making nutrition information more accessible and easier to understand for consumers to help prevent diet-related diseases.2 In Australia and globally, a variety of mandatory and voluntary labelling affects how nutrition information is presented to consumers.

In 2024, the World Health Organization (WHO) conducted public consultation on a draft guideline for nutrition labelling policies.3 This draft guideline emphasises evidence-based, government-led approaches to food labelling that include ingredient lists, nutrient declarations, interpretive front-of-pack labelling, and health claims. The goal is to assist countries in implementing or strengthening food labelling policies in ways that are both effective and feasible, given varying local contexts.4 A finalised guideline has not yet been released.

Various components of food labelling in Australia and around the world are outlined below:

Mandatory Nutrition Labelling

Back-of-pack nutrition declarations are mandatory in many countries, and typically comprise a standardised declaration of nutrients (usually in table format) and a statement of ingredients. Global guidance on these components of the label is contained in Guidelines on Nutrition Labelling5 and the General Standard for the Labelling of Prepacked Foods6, issued by the Codex Alimentarius Commission, the international food standards agency.

Nutrition Information Panel

In Australia and New Zealand, the Nutrition Information Panel (NIP) is regulated by Standard 1.2.8 of the Australian and New Zealand Food Standards Code (Code).7 The Code sets out the information required and how it must be displayed. A NIP must be included on all packaged food (unless subject to a specific exemption) and provides information on the average amount of energy, protein, total fat, saturated fat, carbohydrate, total sugars per serve and per 100g (or 100ml for liquid).

Information ‘per serve’ is provided on the basis of manufacturer recommendation and may differ from what is typically consumed, so provision of information per 100g/100mL can allow a better understanding of a product’s nutritional composition and facilitate comparison between products.

Additional nutrient information is required when particular nutrition content claims are made (for example, the quantity of fibre where a product has a claim that it is a ‘good source’ of fibre).

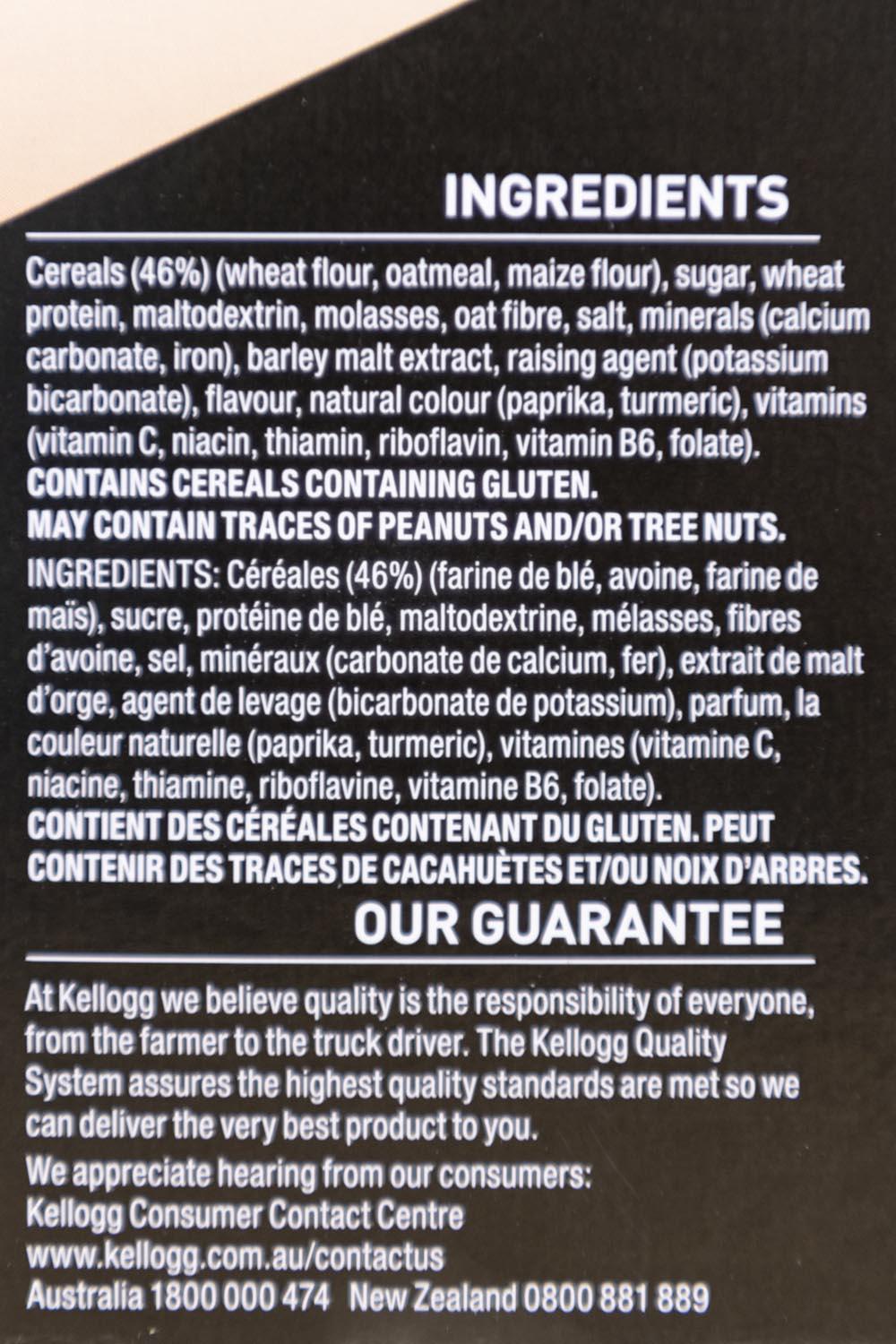

Statement of Ingredients

In addition to the NIP, all products must have a Statement of Ingredients, also regulated under the Code (Standard 1.2.4). This lists ingredients in descending order by weight, including any additives, and preservatives.

Other mandatory labelling

There are also a range of other mandatory labelling requirements in Australia that apply either across the food supply or to particular product types. These include allergen labelling, country of origin labelling, and specific labelling for alcohol products.

Voluntary nutrition labelling

In Australia and New Zealand, manufacturers can voluntarily include nutrition content, health and marketing claims on food labels in addition to mandatory food labelling information.

Nutrition content claims are claims about the content of certain nutrients or substances in a food or drink product. There are two types of nutrition content claims, those that can only be used when certain criteria set out in the Food Standards Code apply (such as ‘no added sugar’, ‘low in fat’ or ‘good source of calcium’), and nutrition content claims that simply describe the presence or absence of certain nutrients or substances (such as ‘free from preservatives’ or ‘contains wholegrains’).8

Health claims describe a link between a food or drink and health benefits (e.g., ‘calcium may reduce the risk of osteoporosis’). General and high-level health claims must be supported by scientific evidence and are only permitted on foods meeting certain nutrient profile criteria.9

Regulation about nutrition content and health claims does not extend to other types of claims on packaging, and there are many types of marketing claims, that are not subject to specific regulation in this way.

Claims are ostensibly used to provide information to consumers, but they typically serve as marketing tactics. In some situations, claims can make a product appear healthier than it really is, giving the product a ‘health halo’ effect and potentially misleading consumers.101112 Evidence suggests that claims can shape perceptions of a product’s healthiness and influence purchasing decisions, regardless of the actual nutritional quality of the products.2

For more information about these claims, their impact and proposed regulation of claims, see the page on Claims on food labels in Australia: health, nutrition content and other marketing claims.

Front of pack nutrition labelling

Recognising that many consumers may find mandatory back-of-Pack nutrition information complex to understand, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends front-of-pack (FOP) nutrition labelling as a tool to promote healthier diets, and lists FOP labelling as a ‘best buy’ policy to address non-communicable disease.1314 FOP labelling systems aim to provide standard, clear information on the nutritional content of packaged food items so consumers can readily identify healthier and less healthy options.15 Effective FOP labels typically employ logos, symbols, colours or ratings to simplify nutrition information for use and understanding . The policy objective is typically two-fold:

- to help consumers make healthier food choices, and

- to encourage industry to reformulate products to create healthier options.16

FOP nutrition labelling systems have now been implemented in many countries around the world in a variety of formats. In Australia and New Zealand, the voluntary Health Star Rating System has been in place since 2014. For more information see Front-of-pack nutrition labelling and Australia’s Health Star Rating System.

Kilojoule menu labelling

Beyond packaged food, some governments have introduced kilojoule menu labelling schemes that require fast food chains and other chain food retail outlets to display the energy content of food and drink in kilojoules at the point of sale. There are mandatory menu labelling schemes in New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia and the Australian Capital Territory.17 There are no requirements for menu labelling in Western Australia, Tasmania and the Northern Territory, however many national businesses voluntarily adopt menu labelling in those jurisdictions.18 Other locations are adopting interpretive menu labels as well, like New York's ‘salt-shaker’ icon, which highlights high-sodium items on menus.19 There is evidence that menu labelling schemes may result in consumers selecting meals with fewer kilojoules.20

For more information on kilojoule labelling in fast food outlets, see the section on Kilojoule labelling in fast food outlets.

Source: NYC Health

Content for this page was updated and reviewed by Gary Sacks and Neha Lalchandani at GLOBE, Institute for Health Transformation, Deakin University. For more information about the approach to content on the site please see About | Obesity Evidence Hub.