Mass media social marketing campaigns

Mass media social marketing campaigns can be an important tool to help shape healthier population behaviours. This section details considerations for effective campaigns, and highlights several major national or state-based Australian campaigns aimed at raising awareness of lifestyle choices that people can make to help prevent excess weight gain and reduce their chronic disease risk, with a focus on promoting healthy eating and physical activity.

Key Evidence

Mass media social marketing campaigns repeatedly deliver health messages to large groups of people, and can be effective at improving health behaviours at the population-level.

To be effective, mass media social marketing campaigns must be noticed, persuasive and remembered.

Examples of major mass media social marketing campaigns in Australia include the nationwide MeasureUp campaign (2008), Go for 2 and 5 in Western Australia (2002 - 2012), and LiveLighter® in Western Australia (2012 – present) and Victoria (2014 - 2016).

It is important that social marketing campaigns are continually evaluated to understand their impact on knowledge, attitudes and behaviours.

What are mass media social marketing campaigns?

Mass media social marketing campaigns deliver an organised set of communication activities using existing mass-reach channels, such as television, radio, print media, online and outdoor media (e.g. billboards), to promote social good. Such campaigns are typically linked to other community-wide interventions, programs and initiatives. Social marketing campaigns addressing public health issues, expose large populations or population sub-groups to health messages repeatedly and over time, with the aim of raising awareness, increasing knowledge and changing health-related behaviour.1 The World Health Organization identifies mass media campaigns within their recommendations to promote healthier eating and increase physical activity.2 Similarly, Australia’s National Obesity Strategy recommends using social marketing to foster healthy social and cultural norms, reduce weight stigma, and support people in making healthier choices.3

Do mass media social marketing campaigns improve diet-related behaviours?

Mass media social marketing campaigns can be effective at improving health behaviours, such as increasing fruit and vegetable consumption, or preventing negative health behaviours, such as reducing smoking rates and preventing HIV infection, typically through small but measurable population-level impacts.456

A systematic review of obesity prevention mass media campaigns in Australia and overseas between 2000 and 2017 found that they can influence adult’s knowledge, attitudes and intentions, especially where campaign awareness is high.7 A recent review of social marketing strategies targeting healthy eating in Australian university environments found that campaigns utilising social media offer a promising strategy for improving knowledge, intention and attitudes towards healthy eating among young adults.8 However, researchers have called for campaign evaluations to assess sustained behaviour change through long-term follow-up.9 They have also recommended linking campaigns to broader prevention strategies targeting policy and environmental changes for more effective change.410

Considerations for an effective mass media social marketing campaign

If they are to be effective, mass media social marketing campaigns must be11:

- noticed: using appropriate media channels and placement to reach the target group

- perceived as persuasive: experienced by the target group as engaging, relevant and/or emotionally affecting

- remembered: seen often enough for them to be recalled and acted upon

Hierarchy of effects model for mass media social marketing campaigns

Adapted from Cavill N, Bauman A. Changing the way people think about health-enhancing physical activity: do mass media campaigns have a role? J Sports Sci. 2004;22(8):771–90 and Kite J, Gale J, Grunseit A, Li V, Bellew W & Bauman A. (2018). From awareness to behaviour: Testing a hierarchy of effects model on the Australian Make Healthy Normal campaign using mediation analysis. Preventive Medicine Reports, 12, 140-7

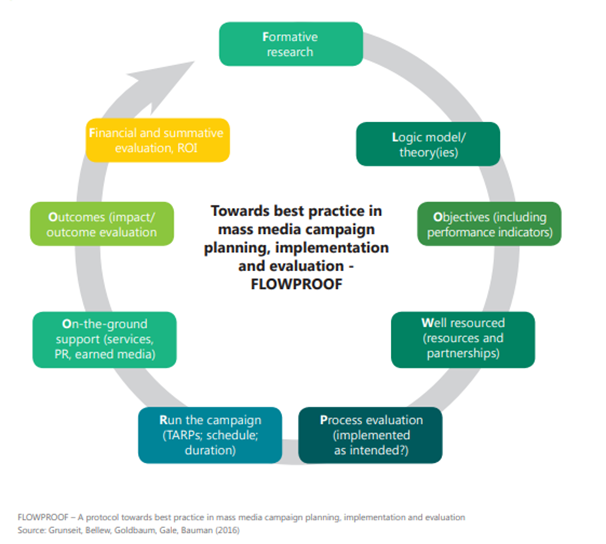

In addition, it is also important for mass media social marketing campaigns to be underpinned by a detailed roadmap to plan, implement and evaluate the campaign – for example, by following the FLOWPROOF protocol.12

FLOWPROOF – A protocol towards best practice in mass media campaign planning, implementation and evaluation

Source: Grunseit A, Bellew B, Goldbaum E, Gale J, Bauman A. Mass media campaigns addressing physical activity, nutrition and obesity in Australia: An updated narrative review. Sydney; The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre. 2016

It is also important to consider potential unintended psychological or behavioural consequences arising from campaigns. Public health campaigns that emphasize personal responsibility in obesity prevention and evoke negative emotions have attracted criticism for potentially contributing to weight stigma.1314 While some studies report increased perceived stigma from such messaging,15161718 others find no clear negative impact.19202122 The effectiveness of particular types of campaign messaging in promoting behaviour change may vary based on individuals’ body weight or perceived weight.232425 A further concern is that overly simplistic messages may overlook the complex causes of obesity, such as genetic, psychological, environmental, economic and social factors, and risk shifting attention away from systemic solutions.26 Campaigns should therefore be carefully designed, pre-tested and evaluated using validated measures with people of varying perceived and actual weight status to avoid reinforcing stigma or undermining policy support.

Major Australian mass media campaigns targeting healthy eating and obesity prevention

A mix of national and state campaigns have run in Australia to inform the public about the health risks of obesity; and to promote positive attitudes and beliefs towards modifiable behaviours that can help achieve or maintain a healthy weight. Evidence indicates that healthy eating education campaigns have had wide reach in Australia, compared with other countries like Canada and USA.27

Further details follow about major Australian mass media campaigns targeting overweight and obesity prevention, at national and state levels, for which published evaluations are available.

National

Measure Up and Swap it, Don’t Stop It

Measure Up and Swap It, Don’t Stop It (2008-2011) were two phases of a major national mass media campaign aimed at encouraging Australians to make healthy changes to diet and physical activity.

The first phase, Measure Up (2008-09), promoted waist circumference as a new way to measure risk of obesity-related chronic diseases and broadly urged people to make healthy changes, such as eating more fruit and vegetables and exercising more. An evaluation of Measure Up in NSW found the campaign increased awareness and knowledge about the link between waistline and chronic disease risk and led to more people measuring their waist, but did not lead to any notable changes in self-reported physical activity or healthy eating behaviours.28

The second phase, Swap It, Don’t Stop It (2011), featured an animated blue balloon character called Eric and encouraged adults to make small, achievable changes by swapping unhealthy behaviours for healthier alternatives, such as swapping large portions for smaller portions and swapping watching television for going for a walk. Across the population, there was moderate awareness of the Swap It, Don’t Stop It campaign but only 16% of Australians surveyed had made at least one swap in the previous six months.29

Researchers said it was likely that environmental changes were needed to supplement such a mass media campaign, in order to make small behaviour changes easier to implement and sustain.

Ad News

http://www.adnews.com.au/campaigns/swap-it-don-t-stop-it

Western Australia

Go for 2 and 5

The Go for 2 and 5 campaign aimed to increase awareness of the recommended intake of fruit and vegetables and increase consumption. The campaign was initially developed and run in Western Australia from 2002 and 2005, then delivered nationally from 2006 to 2012.30 Go for 2 and 5 featured colourful animated characters made from fruit and vegetables and ran on media channels including television, radio, print, as well as at point-of-sale. Evaluation of the state-based WA campaign found it significantly increased correct knowledge of the recommended number of serves of fruit and vegetables and resulted in daily fruit and vegetable intake increasing by 0.8 serves across the WA adult population, with the greatest impact on men who were low consumers of fruit and vegetables.31

WA Health https://healthywa.wa.gov.au/Articles/F_I/Go-for-2-and-5

LiveLighter®

Toxic fat

The LiveLighter® Toxic Fat campaign aimed to illustrate negative health effects of overweight and obesity and encourage small lifestyle changes to increase physical activity and eat a healthier diet. The campaign graphically depicted visceral ‘toxic fat’ around an overweight person’s organs. The campaign was developed by the Department of Health WA and ran first in WA in 2012 on media channels including television, cinema, radio, print and online,22 with campaign advertising complemented by the LiveLighter® website, which offers free tools and resources such as recipes, meal plans and guidance on being more active.32

The principal advertisement explaining ‘why’ overweight was a problem was more commonly recalled than messages showing ‘how’ to change.31 The campaign was perceived by almost all adults who recalled it as believable and making a strong argument for reducing weight.

The proportion of WA adults who reported they would likely meet physical activity recommendations in the immediate term increased significantly from baseline to the second burst of campaign activity.31 There was no significant increase in intentions to change dietary behaviour, however researchers said the overall findings showed mass media campaigns could lead to a shift in attitudes needed to underpin longer-term behavioural change.

Sugary drinks

The second phase of the LiveLighter® campaign targeted sugary drinks, with campaign advertising illustrating the contribution of sugary drinks to the development of visceral ‘toxic fat’ around vital organs. The campaign launched in WA in 2013 using television advertising that was complemented by cinema, radio, print, outdoor and digital advertising.33

The sugary drinks campaign achieved a high level of awareness with about two-thirds of WA adults recalling or recognising it. The campaign led to a significant increase in adults recognising ‘toxic fat’ build up as a health effect of drinking too many sugary drinks. The campaign was associated with a short-term reduction in frequent (4+/week) consumption of sugary drinks among adults. A national cross-sectional school survey found that sugary drink consumption declined more steeply among WA secondary students than students in other states between 2012-2013 and 2018, coinciding with repeated airing of the LiveLighter® "Sugary Drinks" campaign in WA, suggesting the campaign may have hastened declines in teenagers’ sugary drinks consumption.34

Junk food

The LiveLighter® Junk Food campaign launched in 2016 and urged WA adults to reduce their junk food consumption to avoid weight gain and associated chronic disease. A cohort evaluation found that the campaign improved knowledge about the link between overweight and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, reduced unhealthy food purchasing behaviours, and boosted weight-loss confidence among higher body weight adults without reinforcing weight-related stereotypes.19 It also increased support for policy measures promoting healthy eating, demonstrating its effectiveness as a public health advocacy campaign.19

A cost-effectiveness analysis of LiveLighter’s Sugary Drinks and Junk Food campaigns found that the campaign led to reduced sugary drink and sweet food consumption, resulting in modest weight loss, improved health outcomes, and long-term healthcare savings, with the authors concluding that the campaign was cost-effective and offers strong value as part of an obesity prevention strategy.35 Long-running evaluation of LiveLighter® from 2012 to 2029 found the campaign was associated with greater awareness of the health risks of excess body weight, increased vegetable consumption, and reduced intake of sugar-sweetened beverages among adults in Western Australia.36 These results highlight the value of ongoing, well-designed health promotion and education initiatives as key components of a comprehensive approach to obesity prevention.

LiveLighter campaign: https://livelighter.com.au/campaign-and-media

Victoria

Piece of String

The Cancer Council Victoria’s Piece of String television campaign ran in Victoria for six weeks in 2007, targeting adults aged 30 years and older with overweight. The advertisement depicted a domestic scene in which a young girl measured pieces of string and tried unsuccessfully to wrap the string around her father’s waist. It cited evidence that being overweight increased your risk of some cancers and specified target waist measurements that men and women should not exceed.37

An evaluation found that the advertisement increased awareness of the link between obesity and cancer.37 Following exposure to the advertisement, however, respondents were no less likely to classify their weight status as healthy and therefore their perceived risk of cancer did not increase. Researchers said that while the campaign achieved its primary objective of raising awareness of the obesity and cancer link, respondents may have seen the message as more relevant to others, and that barrier was something future campaigns would need to address.

LiveLighter®

The LiveLighter® campaign, developed and launched in WA and detailed above, was also licensed for use in Victoria. First the Toxic Fat campaign ran in 2014 and the Sugary Drinks campaign ran for six weeks in 2015. Paid television advertising was complemented by radio, and digital advertising as well as web-based supporting resources on eating well and being active. Following the Toxic Fat campaign, improvements in knowledge of the health consequences of overweight were reported among Victorian adults.38 A cohort evaluation of the subsequent Sugary Drinks campaign found it led to a significant reduction in the proportion of frequent sugary drinks consumers among the target population of 25 to 49-year-olds in Victoria.39 Among sugary drink consumers with overweight, there was also evidence of increased knowledge of the health effects of drinking sugary drinks and increased water intake.

A television advertisement developed by the Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (VACCHO) and Cancer Council Victoria encouraging Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to reduce their intake of sugary drinks ran on the free-to-air channel National Indigenous Television (NITV) in October 2015 with funding from the Victorian government as part of the LiveLighter® campaign.40 The advertisement depicted an Aboriginal family watching television, including a girl with a can of sugary drink that turned into a stream of sugar as she went to take a sip. It then showed the whole family devouring spoons of sugar, including a girl with rotten teeth, before showing another version of the scene in which the family chose water as a healthy alternative. An evaluation of the campaign found that 52% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people surveyed had seen the advertisement and, of this group, 60% reported cutting down on sugary drinks.41

New South Wales

Make Healthy Normal

The NSW Make Healthy Normal campaign targeted adults with overweight or obesity, or at risk of developing chronic disease, because they did not meet healthy eating or physical activity guidelines. The first phase of the campaign aired in five bursts between November 2015 and June 2016 and centred on two television advertisements, supported by print, outdoor and digital advertising. Campaign messages focused on the ‘problem’ of unhealthy lifestyles becoming normalised and the ‘solution’ of suggested simple lifestyle changes.42 For example, encouraging smaller portions, increased consumption of fruit and vegetables and water, and less sitting. An evaluation found phase one of the campaign increased knowledge on the risks of being overweight and the benefits of lifestyle changes.42

Phase two of the Make Healthy Normal campaign ran from 2017-2018, with the television advertisements airing in a one month burst in September 2017, while digital advertising was continuous throughout the campaign period.10 Evaluation of phase two of the campaign found no consistent positive shifts in outcomes, including behaviour, with the authors calling for complementary environmental and policy strategies to foster behaviour change.10

Content for this page was updated by Jasmine Chan, Deakin University and Gary Sacks, Co-Director at the Global Centre for Preventive Health and Nutrition at Deakin University and reviewed by Belinda Morley and Helen Dixon, Cancer Council Victoria. For more information about the approach to content on the site please see About | Obesity Evidence Hub.